Poisonous Trees

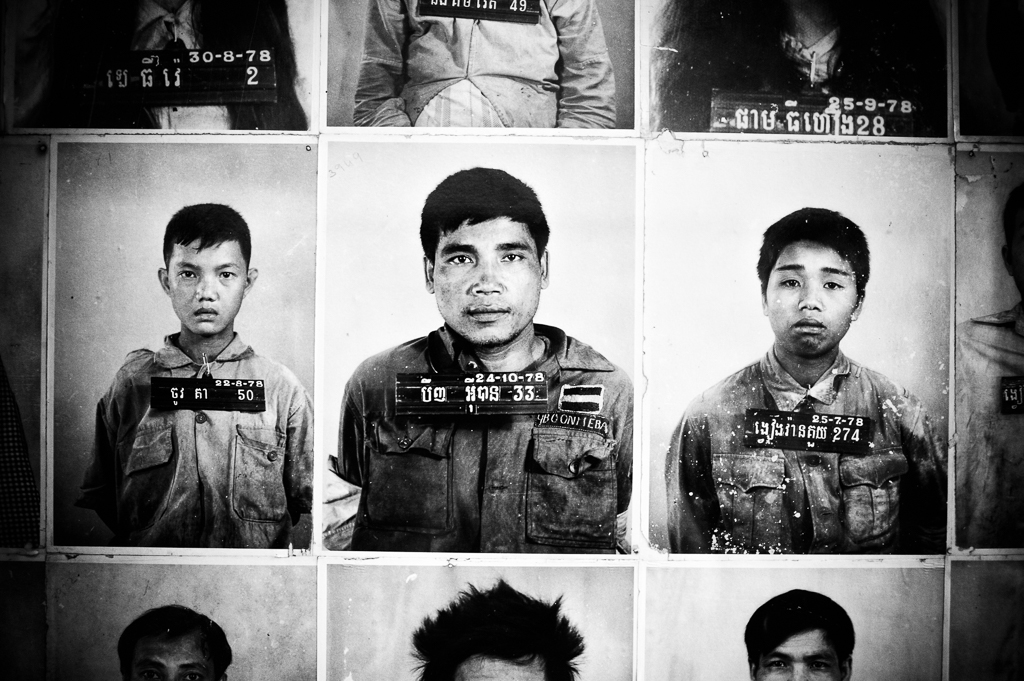

A bitter account of Tuol Sleng, a Cambodian genocide museum.

One would wish that after realizing our human potential for cruelty, we should decide to evolve and stop being our own predators. History, as biased as it can be, doesn’t seem to teach us much, and it is with such disposition that I write this essay in dense, dark, and hopefully loud ink.

Chum Mey, now 85 years old, is one of twelve survivors of the Khmer Rouge detention camp known as S-21, a former high school that is now converted into a Holocaust museum (Tuol Sleng, or “Poisonous Trees”), but back then, it was the final destination for more than twenty thousand people.

Khmer Rouge was the name of the Communist Party of Kampuchea. They ruled between 1975 and 1979, and I never heard of them until my own visit to Cambodia. Most of the world seems to adopt and fixate upon one holocaust (the word itself seems to have been born for Germany and the World War) and never realize that this ‘massive destruction of humans by other humans’ is, unfortunately, a very common occurrence. A quick investigation throws no less than thirty genocides recorded in history.

So far.

A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behaviour, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done. If a story seems moral, do not believe it. If at the end of a war story you feel uplifted, or if you feel that some small bit of rectitude has been salvaged from the larger waste, then you have been made the victim of a very old and terrible lie. There is no rectitude whatsoever. There is no virtue. As a first rule of thumb, therefore, you can tell a true war story by its absolute and uncompromising

- Tim O'Brien

Related Entries

The Bamboo Train

An ancient vehicle, repurposed.

See photographs

The Circus of Siem Reap

The Phare Ponleu Selpak, in Cambodia, brings circus to kids in need

Read article